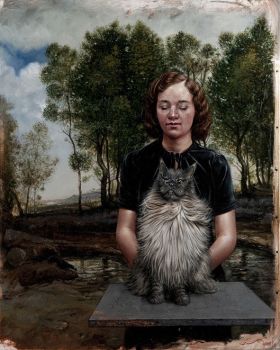

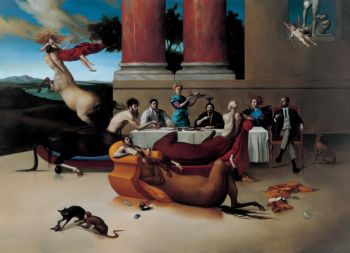

A Charming Lady looks at us, dressed in Gown and Velvet Cloak 1714

Nicolas de Largillière

LienzoPintura de aceitePintura

83 ⨯ 68 cm

Actualmente no disponible a través de Gallerease

- Sobre la obra de arteA charming lady looks at us, dressed in a brocade gown and velvet cloak that is held together with a brooch.

The painter Nicolas de Largilliere (Paris 1656-1746) was the society painter of the eighteenth century. With his portraits he caught an image of the flourishing society under the reign of Louis XIV and XV. This picture is a typical example of a fashionable portrait of Larguilliere in the beginning of the early seventeenhundreds. We know from contracts that the price for a portrait like this, without depiction of the hands, the artist demanded 600 livres.

It is quite difficult though, to identify the ladies he painted, because he reduced and embellished the faces of his clients to satisfy their vanity. This approach of portrayal was a common practice of the era. The famous art critic Roger de Piles ascertained in ‘Cour de Peinture par Principe’ that particularly women were less tolerant of realism when they were to be portrayed. (Cour de Peinture, 1706)

This painting is a characteristic work of the master in a compostion he repeatedly used during his career, with or without hands. It is even very well possible that the clothes worn on the painting were owned by the artist. They happen to appear on more than one occasian in the work of the artist, as can be seen on ladies portraits in the Rau collection, the Bayrische Gemäldesammlungen in Munich and in the Museum of Fine Arts in San Francisco in different arrangements. We also see similar tranquil backdrops here.

Largilliere regularly painted several versions of a portrait, as is the case here. Next to this copy of the hand of the master, another copy of his hand is to be seen in the Musee Cognacq-Jay in Paris. A third version, from the atelier of Largilliere, can be seen in the Mayer van den Bergh Museum in Antwerp.

The identity of the lady,

Although the painting has the name of Jeanne de Robais written on the back in an elegant handwriting, it is not at all certain the portrait is hers. Repeated surveys to identify the elegant lady have failed to date. If she is Jeanne de Robais, she is the daughter of Isaac de Robais, a fabulously rich manufacturer from Abbeville. Isaac’s son Abraham was portrayed by Perroneau in 1767 in pastel. (portrait d’Abraham de Robais, 1767 Musee du Louvre R.F. 4146)

The version in the Musée Cognacq-Jay in Paris traditionaly is called portrait of Madame la Duchesse de Beaufort. She was of English nobility and portrayed during her stay in Paris. Little more of her is known. The atelier version of the painting in the Mayer van den Bergh Museum was obtained from the mayor of Oudenbosch, J.B. Klyn, in 1898. It is said that it concerns a ancestral portrait from a family of French nobility that fled France in 1795. - Sobre el artistaEl pintor Nicolas de Largilliere (París 1656-1746) fue el pintor de sociedad del siglo XVIII. Con sus retratos captó una imagen de la sociedad floreciente bajo el reinado de Luis XIV y XV. Sin embargo, es bastante difícil identificar a las damas que pintó, porque redujo y embelleció los rostros de sus clientes para satisfacer su vanidad. Este enfoque de la representación era una práctica común de la época. El célebre crítico de arte Roger de Piles constató en "Cour de Peinture par Principe" que, en particular, las mujeres eran menos tolerantes con el realismo cuando iban a ser retratadas. (Cour de Peinture, 1706) Nicolas de Largillière le dijo una vez a un amigo que nunca quiso encargos oficiales; los clientes privados eran menos problemáticos y el pago era más rápido. A diferencia de su amigo pintor de la corte Hyacinthe Rigaud, Largillière trabajaba para la clase media adinerada de París. Creció en Amberes, luego trabajó en Inglaterra como asistente de Sir Peter Lely, pintando cortinas y naturalezas muertas y desarrollando una versión brillante del estilo de Anthony van Dyck. Esta formación flamenca impartió las tonalidades cálidas, las pinceladas amplias y espesas y las curvas sinuosas que daban dinamismo a las pinturas de Largillière. Regresó a París en 1682, ganó la membresía de la Académie Royale en 1686 y finalmente se convirtió en su director. A finales de la década de 1680, Largillière había establecido su reputación entre la burguesía. Produjo entre 1.200 y 1.500 retratos en su vida, y gradualmente se volvió menos formal y más relajado al describir la pose y el vestuario. También pintó retratos de grupo para conmemorar ocasiones solemnes, paisajes, naturalezas muertas y obras religiosas. Cuando Largillière le ordenó a su alumno Jean-Baptiste Oudry que representara un ramo de flores completamente blancas, Oudry informó haber aprendido una lección básica sobre el color. Al observar cuidadosamente sus variaciones sutiles y luego tratar de pintarlas, Oudry llegó a comprender cómo expresar reflejos, tonos de gris y sombras como lo hizo su maestro Largillière.

Artwork details

Categoría

Tema

Estilo

Material y Técnica

Colour

Related artworks

Dutch School

Llegada de un holandés de las Indias Orientales a Table Bay18th century

Precio a consultarZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 24Mary Alacoque Waters

'Woman with white Headdress’ after Vermeer1996 - 2006

Precio a consultarGalerie Mia Joosten Amsterdam

1 - 4 / 24Paul Hugo ten Hoopen

Fin de Saison/End of the season1950 - 2000

Precio a consultarKunsthandel Pygmalion

Aris Knikker

Riverview with a village (Kortenhoef, Netherlands)1887 - 1962

Precio a consultarKunsthandel Pygmalion

1 - 4 / 24