A British-colonial Jamaican engraved tortoiseshell comb-case and two combs 1688

Unbekannter Künstler

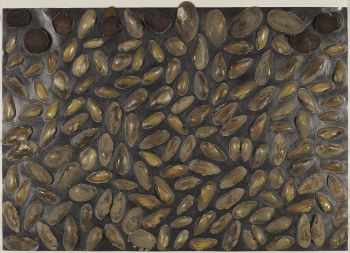

Muschel

19 ⨯ 11 cm

Preis auf Anfrage

Zebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

- Über KunstwerkA British-colonial Jamaican engraved tortoiseshell comb-case and two combs

Jamaica, Port Royal, dated 1688, attributed to Paul Bennett (act. 1670-1692)

The front of the case engraved with the coat-of-arms of Jamaica, and inscribed IAMAICA 1688. The reverse is engraved with a palm tree and breadfruit. Both combs have been restored in the past with small charming brass mounts. The engravings have been accentuated with lime, with some traces of yellow colouring, which was used to make it look like inlaid gold.

H. 19.5 x W. 11.3 x D. 1.1 cm (case)

Provenance:

The Henrietta and Chauncey Goodrich Collection (since the 1920s)

Private collection, United Kingdom

Jamaican Engraved Tortoiseshell

A Beautiful but Poignant expression.

After England’s conquest of Jamaica on the Spanish colonists in 1655, Port Royal developed into a large city and the thriving commercial centre of (the then archipelago) Jamaica. However, this all ended when a massive earthquake devastated the city and swept two-thirds of it under the sea in 1692. Combs made of materials such as ivory, wood, and horn were quite common in medieval and early modern Europe and a well-known status symbol. These tortoiseshell combs are objects created from familiar forms to reflect new cultural structures in a quickly changing society.

‘INDUS UTERQUE SERVIET UNI’

Taken home after the ‘colonial adventure’ as mementoes of Jamaica, they proved their owner’s worldliness and newly gathered fortunes by perfectly balancing the ‘exotic’ and the familiar, thus being a tool to obtain a higher social status upon arrival. The tortoiseshell was engraved with tulips and sunflowers, inspired by late-17th-century English embroidery. Often, they are engraved with the new coat-of- arms of Jamaica as well. These were granted in 1662, seven years after Britain seized the island in 1655 by Admiral William Penn and General Robert Venables and eight years before Spain’s official recognition of British claim to the island in the Treaty of Madrid, 1670. The arms are often combined with crops that – together with the labour of enslaved people (African and Indigenous) - made the economy thrive, such as sugar cane, cotton, fruit trees and coconut palms. Prior to Jamaica securing independence in 1962, the coat-of-arms reflected the Latin motto “INDUS UTERQUE SERVIET UNI” meaning “The two Indians will serve as one”. This refers to the collective servitude of the Taino and Arawak Indigenous to the British colonisers. The combs taken to England as a ‘souvenir’, therefore, also served as propaganda of the colonial ideas.

The narrow-toothed comb probably was intended for extracting lice, and the wide-toothed comb was for fixing wigs. It seems, however, that they were not for use but for show and display only. These combs could have been made for clients of mixed descent. However, it is known that British company officials often had children with one or more of their enslaved women. These children would become an integral part of upper-class society and would sometimes even move to England. Such an elaborate culture of comb-making might well be connected to the African roots of this community.

The Hawksbill Turtle’s shell was a widely used material and can be regarded as plastic avant la lettre, having the ability to bend when heated. These turtles were common in the oceans until they were hunted down almost to extinction, only to be (successfully) protected in the 20th century. This set is a beautiful but poignant expression of a painful cultural moment. Bought with wealth generated by enslaved Africans and indigenous peoples, it embodies the English appreciation of Jamaica’s glorious culture and natural history and the simultaneous savaging of it.

Attribution: Bennett or Comberford?

The Institute of Jamaica in London has eleven tortoiseshell combs, one large box with combs and one powder box. The first comb for the Institute of Jamaica in London was purchased by members of the West India Committee in 1923. It was described by H.M. Cundall in the West India Committee Circular from 1923 as “probably one of the earliest art objects made in the British West Indies displaying European influence.” The tortoiseshell works in the Jamaica Institute’s collection are thought to be from the hands of two craftsmen working in Port Royal between circa 1671-1684 and 1688- 1692, respectively. The present box is linked to the first group. Philip Hart, in his article Tortoiseshell Comb Cases, for the Jamaica Journal, reveals that research found an Englishman called Paul Bennett, in Port Royal, listed in 1673 as a comb maker.Therefore, it’s likely that Bennett was the maker of this first group, and an apprentice or assistant was the maker of the second group. Other works supposedly by Paul Bennett include the Sir Cuthbert Grundly comb case, dated 1672, a round powder box lid and comb case in a private U.S. collection, dated 1677, and the ‘Lady Smith’ casket, which is considered the artist’s masterpiece.

The earliest known comb-case with two combs, inscribed Sarah Henley and dated 1670, was sold by us in 2023 and can now be found in the collection of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts (see: Guus Röell & Dickie Zebregs, Uit Verre Streken, March 2023, p. 43, no. 14).

New research by Ms. Jade Lindo, a V&A/RCA History of Design MA student 2021-22, proved that the other craftsman making tortoiseshell combs was Matthew Comberford. Most boxes, cases and combs have a very particular style of engraving, but the present comb case with silver mounts shows a whole different style. Hence, it could have been made by Bennett’s colleague-comb maker Comberford – and the pun was probably intended. Another comb-case of the same quality and style, but dated 1688, was sold in New York in 2018. Remarkably, the comb in this case, too, was different in style than the case itself, which might point towards a cooperation between Bennett and Comberford of some sort. Did they own the company together, or was Comberford perhaps the successor of the business?

Literature:

Philip Hart, ‘Tortoiseshell Comb Cases: a 17th century Jamaican Craft’ in Jamaica Journal, the quarterly journal of the Institute of Jamaica, Vol 16, No 3, August 1983

H.M. Cundall, “Early Jamaican Handicraft”, in: The West India Committee Circular, 29th March, 1923

Frank Cundall, “Tortoiseshell carving in Jamaica”, in: The Connoisseur, July 1925, p.154

Frank Cundall, Tortoiseshell - Carving: A Notable Specimen in Jamaica, London, National Art Library, 1929

Jen Cruse, “Colonial Craftsmanship in Jamaica, in America in Britain” in: Journal of the American Museum in Bath, XXXIX, pp.18-25

Evelyn Haertig, Antique Combs and Purses, Carmel CA, Gallery Graphics, 1983

Donald F. Johnson, “From The Collection” in: Winterthur Portfolio, 43,2009, pp. 313- 334 - Über Künstler

Es kann vorkommen, dass ein Künstler oder Hersteller unbekannt ist.

Bei einigen Werken ist nicht zu bestimmen, von wem sie hergestellt wurden, oder sie wurden von (einer Gruppe von) Handwerkern hergestellt. Beispiele sind Statuen aus der Antike, Möbel, Spiegel oder Signaturen, die nicht klar oder lesbar sind, aber auch einige Werke sind überhaupt nicht signiert.

Außerdem finden Sie folgende Beschreibung:

•"Zugeschrieben …." Ihrer Meinung nach wohl zumindest teilweise ein Werk des Künstlers

•„Atelier von ….“ oder „Werkstatt von“ Ihrer Meinung nach eine Arbeit, die im Atelier oder in der Werkstatt des Künstlers, möglicherweise unter seiner Aufsicht, ausgeführt wurde

•„Kreis von ….“ Ihrer Meinung nach ein Werk aus der Zeit des Künstlers, das seinen Einfluss zeigt, eng mit dem Künstler verbunden, aber nicht unbedingt sein Schüler

•"Art von …." oder „Anhänger von ….“ Ihrer Meinung nach eine Arbeit, die im Stil des Künstlers ausgeführt wurde, aber nicht unbedingt von einem Schüler; kann zeitgenössisch oder fast zeitgenössisch sein

•„Art von ….“ Ihrer Meinung nach ein Werk im Stil des Künstlers, aber späteren Datums

•"Nach …." Ihrer Meinung nach eine Kopie (jegliches Datums) eines Werks des Künstlers

• „Unterzeichnet …“, „Datiert …“. oder „Beschriftet“ Ihrer Meinung nach wurde das Werk vom Künstler signiert/datiert/beschriftet. Das Hinzufügen eines Fragezeichens weist auf einen Zweifel hin

• „Mit Unterschrift …“, „Mit Datum …“, „Mit Aufschrift ….“ oder „Trägt Unterschrift/Datum/Beschriftung“ ihrer Meinung nach die Unterschrift/Datum/Beschriftung von jemand anderem als dem Künstler hinzugefügt wurde

Sind Sie daran interessiert, dieses Kunstwerk zu kaufen?

Artwork details

Related artworks

- 1 - 4 / 12

Unbekannter Künstler

EIN UNGEWÖHNLICHES INDONESISCHES SILBERGERICHTlate 17th

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unbekannter Künstler

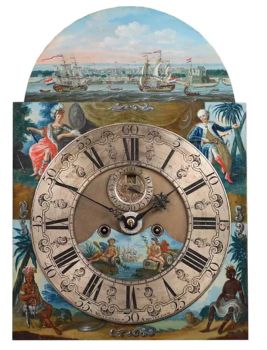

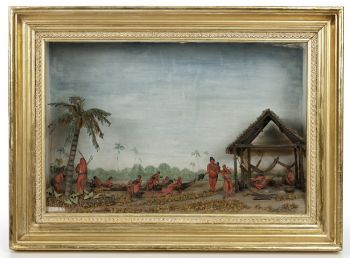

A Surinam-themed Amsterdam long-case clock1746 - 1756

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Kuratiert von

Kuratiert vonGallerease Magazine

Unbekannter Künstler

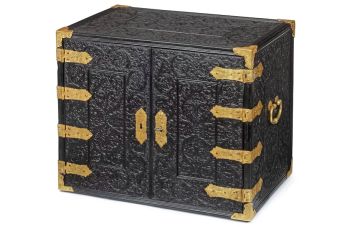

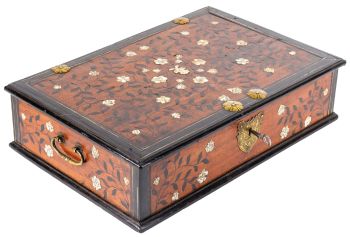

Japanese transition-style lacquer coffer 1640 - 1650

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

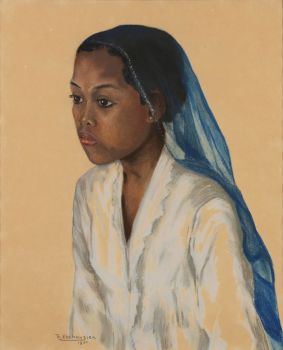

Paulus Franciscus Kromjong

Blumen vor Arearea Aka (Freude) von Gauguin '20th century

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unbekannter Künstler

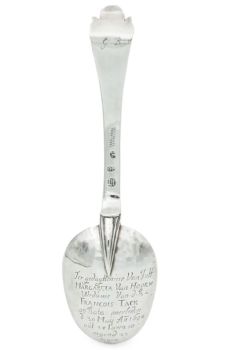

A silver spoon commemorating Juff’ Margareta van Hoorn1656 - 1694

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 24Unbekannter Künstler

The Stamford Raffles Secretaires.1800 - 1813

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unbekannter Künstler

EIN GILT-SILBER SRI LANKAN DOKUMENT SCROLL CONTAINER19th century

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unbekannter Künstler

EIN JAPANISCHES MODELL EINES NORIMONO, EINES PALANQUINS1650 - 1700

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unbekannter Künstler

EINE SAMMLUNG VON VIER SRI LANKAN IVORY BIBELKÄSTCHEN18th century

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 24- 1 - 2 / 2

Unbekannter Künstler

The bell of the VOC fortress in Jaffna, Sri Lanka1747

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Kuratiert von

Kuratiert vonDanny Bree

Paulus Franciscus Kromjong

Blumen vor Arearea Aka (Freude) von Gauguin '20th century

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

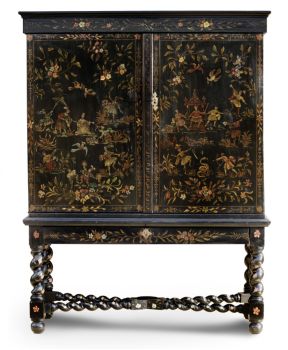

Unbekannter Künstler

Japanese transition-style lacquer coffer 1640 - 1650

Preis auf AnfrageZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 12