An important Peruvian silver plaque with hammered decoration of the legendary wedding of Martin de L 1675 - 1775

Artiste Inconnu

Argent

22 ⨯ 29 cm

Prix sur demande

Zebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

- Sur l'oeuvre d'artAn important Peruvian silver plaque with hammered decoration of the legendary wedding of Martin de Loyola and Beatriz Clara Coya, ‘the Spanish Prince and the Inca Princess’

Viceroyalty of Peru, late 17th/18th century or later

The plaque depicts the famous couple surrounded by a feline, dog, monkey, parrot, flowers, child (possibly their daughter Ana María Lorenza de Loyola) and a servant holding an umbrella (achiwa). It was likely used in wedding ceremonies. The plaque could have been a breastplate and part of the attire of either an Inca priest who officiated weddings or a dancer participating in a wedding.

H. 22 x W. 29 cm

Provenance:

Collected by a KLM (Royal Dutch Airways) pilot in the 1970s

Amsterdam antiques trade

Exhibited:

Ahead of her Time: Pioneering Women from the Renaissance to the Twentieth Century, 5-12-2023 - 10-2-2024, Robilant+Voena, New York

There was an editorial error in our Tefaf 2023 catalogue and Mr. Mujica was misquoted. We apologise for the mistake.

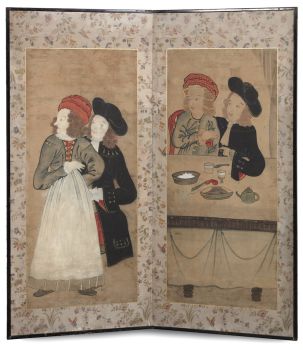

Don Martín García Óñez de Loyola (1549-1598) and Beatriz Clara Coya (1556-1600) were assumed to be the first married persons in Peru who were from a different royal lineage. One of the Conqueror and the other of the Conquered. Martín was a Spanish soldier of noble descent and the Royal Governor or Captain General of Chile. Beatriz was a ñusta, an Inca princess - the last Inca princess, to be exact. On the plaque, she wears dress robes typically worn by Inca nobility. The couple can be identified by a set of very distinguishable iconographical aspects in the art history of South America.

Princess Beatriz became a symbol of Inca royalty. She was a valuable match, not just because of her royal lineage's political weight but also due to her territorial and political influence. She inherited strategic valleys such as Yucay, Pissac, and Xaquixaguana from her father and even governed Chile. During her life, numerous sources speak about her, of which one is awe-inspiring: “The value, the virtues and the being of all the Incas belong to her because she is a descendant of all these powerful Lords; thanks to her, her ancestors enjoy eternal memory.” (Historia del origen y genealogía real de los Reyes Inças del Peru, Martín de Murúa, 1590). Holding this position was another way of demonstrating her royal status. As women in the Habsburg Empire who governed territories acted as viceroys or served as regents and were usually from the royal family.

The plaque relates to a painting in the Museo Pedro de Osma in Peru depicting the marriage dating from circa 1718. Since the late 17th century, such paintings have been used in churches in South America to gain more followers amongst the indigenous population. After all, if an Inca Princess married a Spaniard in a Catholic church, it would surely be safe to convert to Christianity. The marriage between the couple was forbidden when it happened, and so were the (popular) depictions of it that emerged right after. Only in the 17th century did the Church realise its potential and use the imagery as ‘propaganda’. Whether this breastplate is from before or after this time is not certain, but suggesting it was used in forbidden weddings between Inca and Spanish people is tempting.

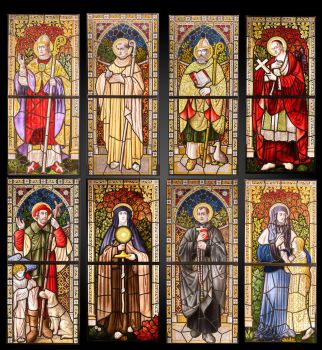

The Jesuits of Cusco devised this painting. It depicts two marriages that linked the Inca royal line with the line of two patriarchs of the Society of Jesus. This painting has three main groups. The first, to the upper left, consists of three of the last surviving members of Inca royalty. From left to right, Sayri Túpac, son of Manci Inca, who upon his father’s death was recognised as Inca by the Spaniards; his brother Túpac Amaru I, leader of the last bastion of Inca resistance during the Conquest, and Cusi Huarcay, Beatriz Ñusta’s mother, who upon the death of her husband, Sayri Túpac, fought for recognition of her rights as part of Inca nobility. The second group, on the lower left, shows six individuals. To the left is the couple composed of Beatriz Ñusta, the last Inca princess, wearing clothing with symbolism usual for Inca nobles, and Captain Martín García de Loyola, who married in 1572. Martín García de Loyola received, by order of Viceroy Toldeo, the princess’ hand as a reward for defeating the last stronghold of Inca resistance, led by Túpac Amaru, Beatriz’ uncle. To the right is their daughter, Ana María Lorenza de Loyola, with her husband, Juan Enríquez de Borja. Between both couples, we can see, to the right, St. Ignatius of Loyola, and to the left, St. Francis Borgia, Third Superior General of the Society of Jesus, and grandfather of Juan Enríquez de Borja. The third group, to the upper right, shows the wedding between Juan Enríquez de Borja and Ana María Lorenza de Loyola, held in Madrid in 1611. The painting narrates events that took place during the 16th and 17th centuries and was painted in the 18th century to underline the union between Inca nobility and the Society of Jesus, thus reclaiming the legitimacy of the privileged position held by both parties within the colonial order, in a time when this privilege was under threat.

During the troubled era of Spanish conquest and dominance, the foundation was laid for a new way to lead the destinies of the local people. Military actions and treaties with the Inca elite and local groups consolidated the power of colonial authorities. The collapse of the Inca rule throughout the wide territory of Tahuantinsuyo unleashed a process in which local and regional traditions adapted to the new cultural models promoted by the Spanish Crown. This constant change and cultural adaptation persist to the present day and is part of the wider phenomenon of acculturation and syncretism that inevitably arises whenever two different civilisations clash. Peru’s process was, however, one of a kind since it took place between two cultures previously unknown to one another. The survival of ancient traditions is reflected in the adaptation of certain elements, such as the tupu and the quero. The latter contributed to preserving the tradition of toasts using pairs of vessels and became a vehicle for transmitting the old glories and customs of the Inca to their descendants. The fall of Tahuantinsuyo led to a process of adaptation and alliances between local inhabitants, with their different regional traditions, and conquistadors, who brought their own cultural mores. Although the native population was forced to accept the new political, economic and religious rules, it also managed to preserve many of its beliefs, images and customs. The Inca elite, which held a privileged position during the Viceroyalty, continued using elements that partly defined its identity and hierarchy. Similarly, the native population preserved its religious images and Andean rituals under Western devotional forms.

On this painting we see Beatriz’ royal family on the left, in traditional noble clothing. The umbrellas (or achiwa), show their noble status. This can be seen in the silver plaque too, a servant holding an umbrella above Beatriz’s head. Her skin is darker, emphasising her origins. The Cusco School Escuela cuzqueña, was a Roman Catholic artistic tradition based in Cusco, Peru (the former capital of the Inca Empire) during the colonial period, in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

There was an editorial error in our 2023 catalogue, where Mr. Mujica was misquoted. We apologise for the mistake.

*The Dutch Institute for Gold and Silver in Gouda has analysed the silver in four places. First, they state that the

alloy of the plaque is very high in silver and has a small percentage of copper, tin and gold. However

consistent in the alloy, the percentages of it are not consistent all over the plaque, which points out that the

plaque probably was made from scrap silver that could not be heated enough for a complete mix. The

technique and absence of other metals in the alloy point towards the given date. The fourth analysis is that of

the restoration flap to the back, which also has a pure alloy.*

Sources:

Ana Maria Lorandi, Spanish King of the Incas: The Epic Life of Pedro Bohorques, University of Pittsburg Press, 2005, pp. 43, 61-62.

Fray Martín Murúa, Historia del origen y genealogía real de los Reyes Inças del Perú, Madrid, c. 1592- 1598, 1946.

Images:

*Marriages of Martin de Loyola to Beatriz Ñusta, and Juan de Borja to Lorenza Ñusta de Loyola*, Anonymous painter, 1718, Museo Pedro de Osma, Peru

*The Marriage of Don Martín García de Loyola and the Inca ñusta Beatriz Clara Coya, daughter of Sayri Túpac; parents of the first Marchioness of Oropesa*, Anonymous painter, late 17th century, Church of la Compañía de Jesús, Cusco - Sur l'artiste

Il peut arriver qu'un artiste ou un créateur soit inconnu.

Certaines œuvres ne doivent pas être déterminées par qui elles sont faites ou elles sont faites par (un groupe d') artisans. Les exemples sont des statues de l'Antiquité, des meubles, des miroirs ou des signatures qui ne sont pas claires ou lisibles, mais aussi certaines œuvres ne sont pas signées du tout.

Vous pouvez également trouver la description suivante :

•"Attribué à …." A leur avis probablement une oeuvre de l'artiste, au moins en partie

•« Atelier de …. ou « Atelier de » À leur avis, une œuvre exécutée dans l'atelier ou l'atelier de l'artiste, éventuellement sous sa direction

•« Cercle de… ». A leur avis une oeuvre de la période de l'artiste témoignant de son influence, étroitement associée à l'artiste mais pas forcément son élève

•« Style de … ». ou "Suiveur de ...." Selon eux, une œuvre exécutée dans le style de l'artiste mais pas nécessairement par un élève ; peut être contemporain ou presque contemporain

•« Manière de… ». A leur avis une oeuvre dans le style de l'artiste mais d'une date plus tardive

•"Après …." A leur avis une copie (quelle qu'en soit la date) d'une oeuvre de l'artiste

•« Signé… », « Daté… ». ou « Inscrit » À leur avis, l'œuvre a été signée/datée/inscrite par l'artiste. L'ajout d'un point d'interrogation indique un élément de doute

• "Avec signature ….", "Avec date ….", "Avec inscription …." ou "Porte signature/date/inscription" à leur avis la signature/date/inscription a été ajoutée par quelqu'un d'autre que l'artiste

Êtes-vous intéressé par l'achat de cette oeuvre?

Artwork details

Related artworks

- 1 - 4 / 12

Artiste Inconnu

A Dutch colonial Indonesian betel box with gold mounts1750 - 1800

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

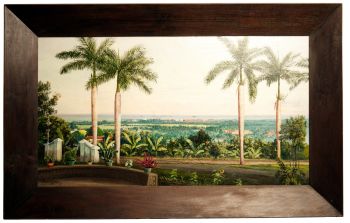

Artiste Inconnu

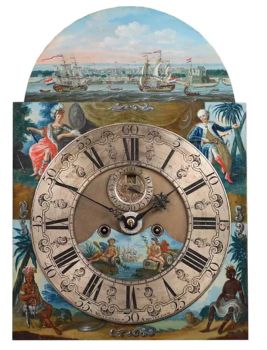

A Surinam-themed Amsterdam long-case clock1746 - 1756

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Sélectionné par

Sélectionné parGallerease Magazine

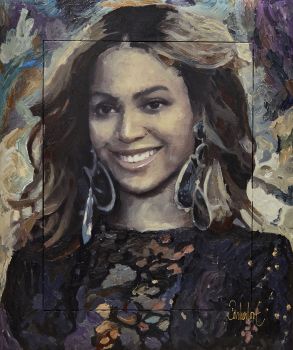

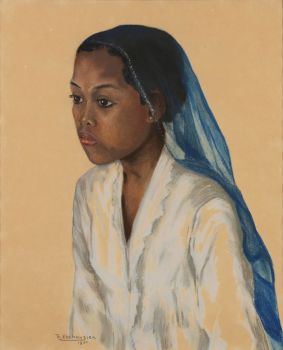

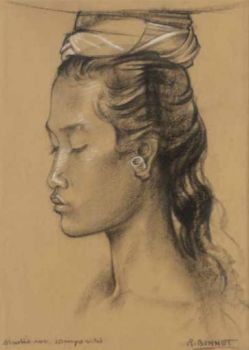

Paulus Franciscus Kromjong

Fleurs devant Arearea Aka (joie) par Gauguin '20th century

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

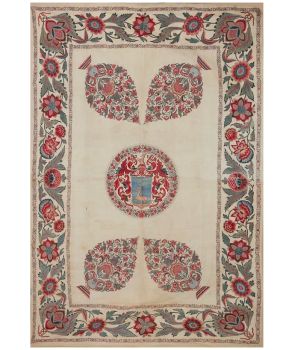

Artiste Inconnu

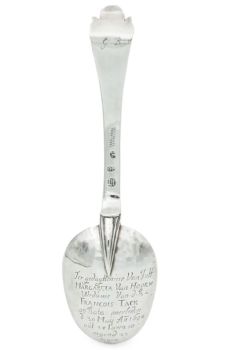

A silver spoon commemorating Juff’ Margareta van Hoorn1656 - 1694

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Artiste Inconnu

UN PLAT EN ARGENT LOBBED INDONÉSIEN INSOLITElate 17th

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 24Artiste Inconnu

UNE COLLECTION DE QUATRE BOÎTES À BIBLE EN IVOIRE SRI LANKAN18th century

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

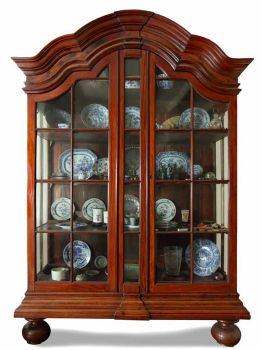

Artiste Inconnu

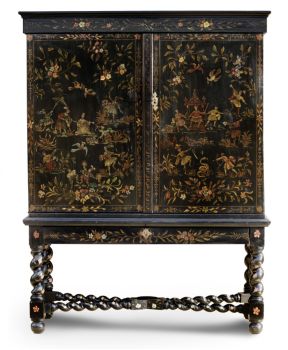

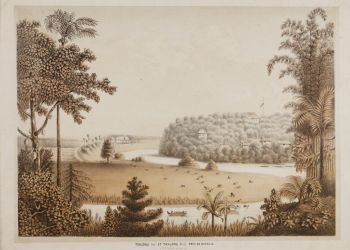

The Stamford Raffles Secretaires.1800 - 1813

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

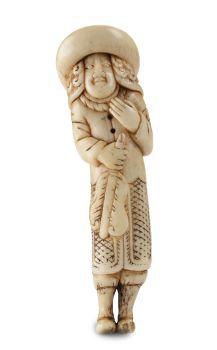

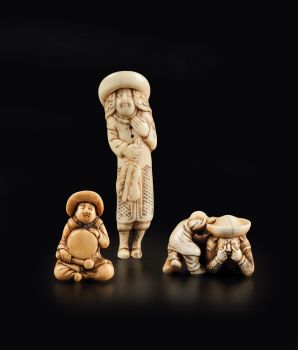

Artiste Inconnu

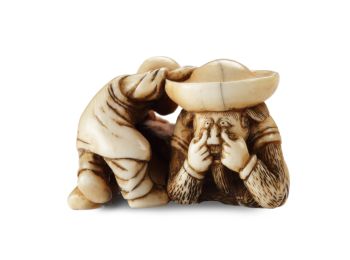

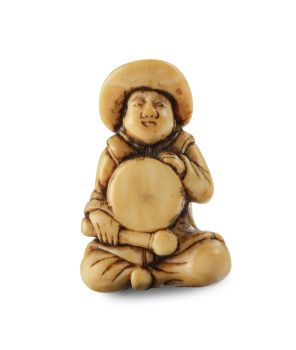

UN FILET D'IVOIRE D'UN DUTCHMAN TENANT UN COCKEREL18th century

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

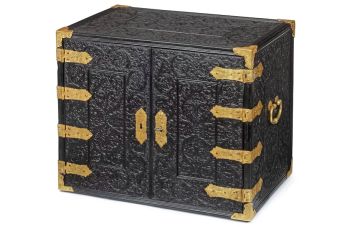

1 - 4 / 24Artiste Inconnu

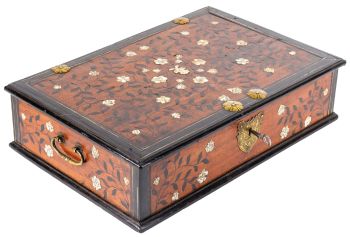

Japanese transition-style lacquer coffer 1640 - 1650

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Artiste Inconnu

A Surinam-themed Amsterdam long-case clock1746 - 1756

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Sélectionné par

Sélectionné parGallerease Magazine

Artiste Inconnu

A Dutch colonial Indonesian betel box with gold mounts1750 - 1800

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 24- 1 - 4 / 24

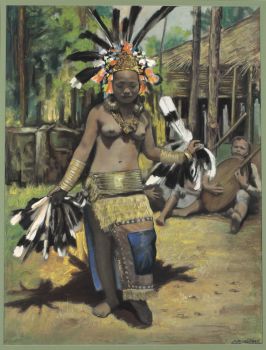

Artiste Inconnu

GRANDE PEINTURE INDIENNE IMPORTANTE ET RARE `` STYLE D'ENTREPRISE '' SUR IVOIRE REPRÉSENTANT UN DÉFI1850 - 1900

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Sélectionné par

Sélectionné parDanny Bree

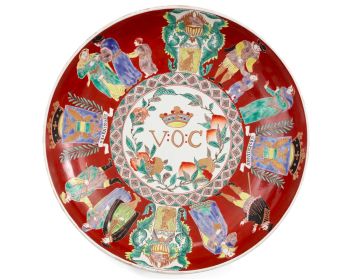

Artiste Inconnu

A large Japanese Imari porcelain 'VOC Groningen' dish1800 - 1925

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Artiste Inconnu

Néerlandais en miniature18th century

Prix sur demandeZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 12