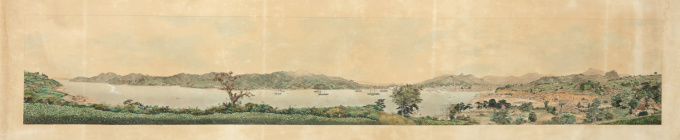

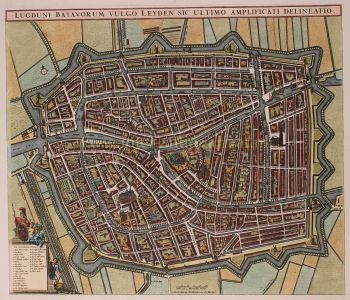

Grande pintura panorâmica da baía de Nagasaki 19th century

Artista Desconhecido

PapelPapel japonês

70 ⨯ 270 cm

Atualmente indisponível via Gallerease

Zebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

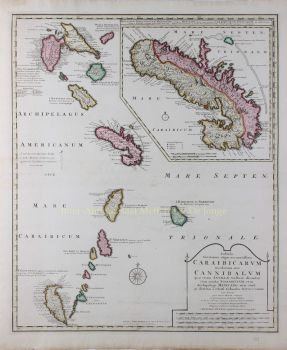

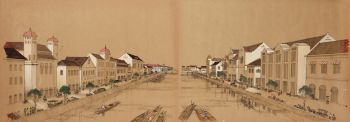

- Sobre arteUNKNOWN JAPANESE ARTIST (19TH CENTURY)

Large panoramic painting of the bay of Nagasaki, painted after photographs taken by

Pierre Rossier (Swiss 1829-c. 1886), in 1860 (circa 1860)

Watercolour and gouache on five sheets of paper laid down on canvas, 70 x 270 cm

Note:

Pierre Rossier was a pioneering Swiss photographer. He was commissioned by the London firm of Negretti and Zambra to travel to Asia and document the progress of the Anglo-French troops in the Second Opium War of 1858-1860. Although he failed to join the military expedition, he remained in Asia for several years, producing the first commercial photographs of China, the Philippines, Japan and Siam. In 1858 Rossier arrived in Hong Kong where he took photos mainly in and around Canton.

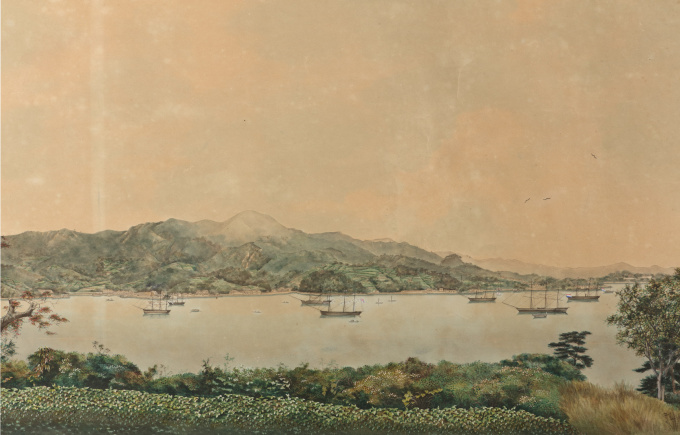

In November 1859, Negretti and Zambra published fifty of the views Rossier had made there. In 1858 or 1859 Rossier travel to the Philippines where he photographed, among other things, the Taal Vulcano. In 1859 he was in Japan, making photographs first in Nagasaki, where he took a portrait of Philipp Franz von Siebold’s son Alexander, then in Kanagawa, Yokohama and Edo. In June 1860 he was in Shanghai to join the Anglo-French expedition, but he was too late; other photographers had already taken his place. He returned to Nagasaki where he took the panoramic view, of eight photo’s, of the harbour of Nagasaki on behalf of the British Consul, George S. Morrison, for which he was paid £70. Mr Morrison justified his payment to the British authorities by writing: “Considering that it might be useful and interesting to Her Majesty’s Government to possess an accurate representation of (Nagasaki) port, I have taken advantage of an occasion not likely soon again to present itself, to obtain these views by a professional photographer here for the moment, Mr. Rossier, an employee of the firm of Negretti & Zambra of London”.

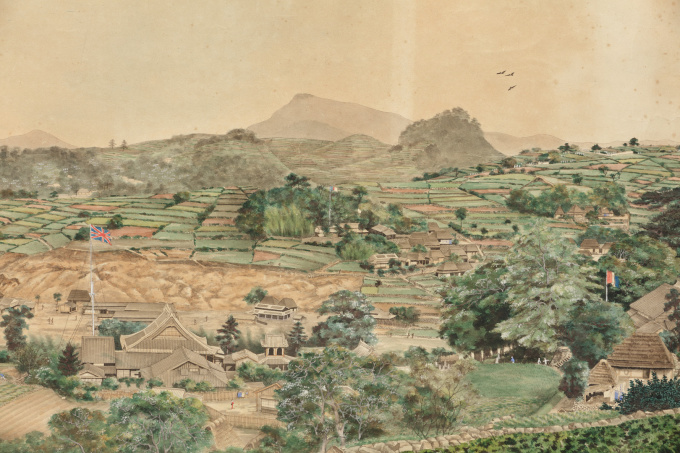

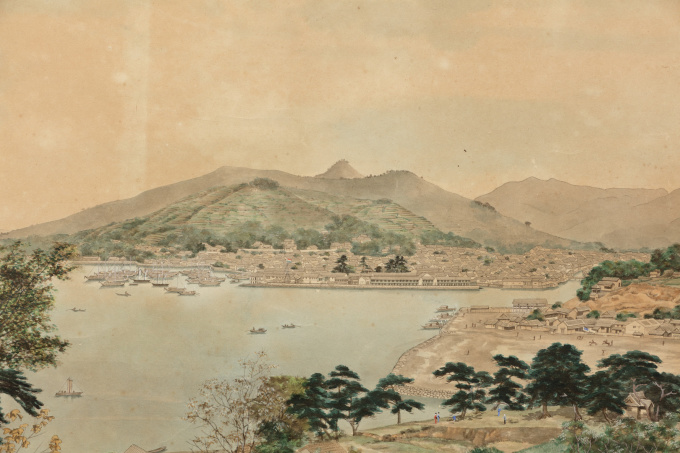

In the painting, the Dutch flag can (still) be seen flying over the small island of Deshima. To the right, the English, French and Russian flags are flying from their temporary Consulates and warehouses.

Later a margin of the shallow seafront was reclaimed from the sea and linked with Deshima island to form the site of future foreign settlement. In the bay are various ships anchored with Dutch and English flags. One is flying the Japanese flag. This is probably the Soembing presented by the Dutch to Japan in 1855, renamed Kankõ- Maru and decommissioned in 1876. The Kankõ-Maru was the first modern steam- warship for the Japanese navy on which the Dutch trained the Japanese seamen in ship-manoeuvering, artillery and general marine technology.

On 1st July 1859, Nagasaki was opened to foreign trade and the Dutch and Chinese could now conduct their business as free merchants. The Dutch no longer were confined as prisoners to the small fan-shaped island of Deshima, but at the same time lost their monopoly of trade with Japan. But also the Japanese officials, through whom that trade had passed, lost their valuable concessions without any compensating advantages and so did the Chinese who lost the monopoly they had acquired in certain lines. Therefore the Japanese officials, together with the Chinese, placed all manner of hindrances in the way of the newcomers crashing into their business. In the face of all this, the newcomers were not able to open up international trade in Nagasaki within days or even months. The Britsh, French, American and Russian consuls who had settled in Nagasaki after July 1859, were busy for months writing blistering notes of protest to the Japanese authorities at the difficulties which were being placed in the way of their trade. Gradually, however, the transition came about, and Nagasaki became a vital centre of Japan’s overseas trade. Initially, the Dutch still had their quarters on Deshima, and the newly arrived merchants from other countries were lodged in small Japanese houses. The English Consulate was located in a Japanese temple for five years until a suitable site on the seafront was available. The Dutch continued to rent Deshima until 1863. Thereafter it became part of the larger waterfront where the new foreign settlements were located. For the first two years, all diplomatic correspondence was carried out with the Japanese in Dutch, but gradually English took over. In the first six months over fifty British trading vessels alone came into port and Nagasaki also became a busy port for whalers, mostly American, that came into refit. At times there were as many as fifteen or more whalers in the harbour at one time. However, by 1868 Yokohama, closer to Edo, had taken over as the main port to Japan and by then the foreign consulates had moved there. - Sobre artista

Pode acontecer que um artista ou criador seja desconhecido.

Algumas obras não devem ser determinadas por quem são feitas ou são feitas por (um grupo de) artesãos. Exemplos são estátuas dos tempos antigos, móveis, espelhos ou assinaturas que não são claras ou legíveis, mas também algumas obras não são assinadas.

Além disso, você pode encontrar a seguinte descrição:

•"Atribuído a …." Na opinião deles, provavelmente uma obra do artista, pelo menos em parte

• “Estúdio de…” ou “Oficina de” Em sua opinião um trabalho executado no estúdio ou oficina do artista, possivelmente sob sua supervisão

• "Círculo de ..." Na opinião deles, uma obra da época do artista mostrando sua influência, intimamente associada ao artista, mas não necessariamente seu aluno

•“Estilo de…” ou “Seguidor de…” Na opinião deles, um trabalho executado no estilo do artista, mas não necessariamente por um aluno; pode ser contemporâneo ou quase contemporâneo

• "Maneira de ..." Na opinião deles, uma obra no estilo do artista, mas de data posterior

•"Depois …." Na opinião deles uma cópia (de qualquer data) de uma obra do artista

• “Assinado…”, “Datado…” ou “Inscrito” Na opinião deles, a obra foi assinada/datada/inscrita pelo artista. A adição de um ponto de interrogação indica um elemento de dúvida

• "Com assinatura ….”, “Com data ….”, “Com inscrição ….” ou “Tem assinatura/data/inscrição” na opinião deles a assinatura/data/inscrição foi adicionada por outra pessoa que não o artista

Você está interessado em comprar esta obra de arte?

Artwork details

Related artworks

Artista Desconhecido

Copo de beber Cristallo façon de Venise1600 - 1650

Preço em pedidoPeter Korf de Gidts - Antiquairs

1 - 4 / 12- 1 - 4 / 24

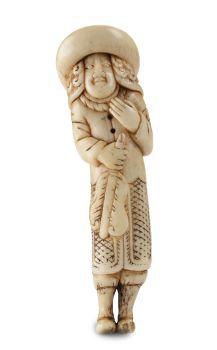

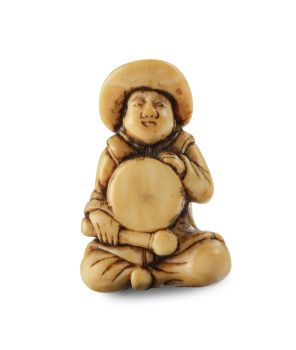

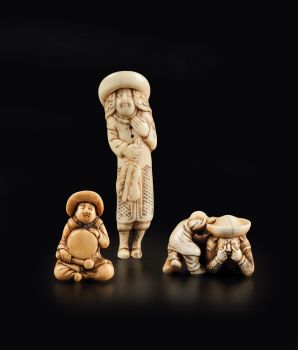

Artista Desconhecido

Holandeses em miniatura18th century

Preço em pedidoZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 24- 1 - 4 / 24

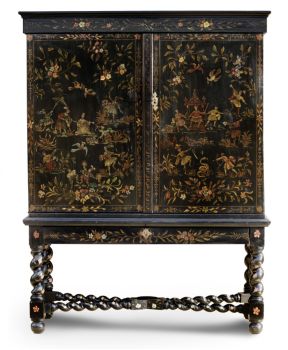

Artista Desconhecido

Japanese transition-style lacquer coffer 1640 - 1650

Preço em pedidoZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 12