The Stamford Raffles Secretaires. 1800 - 1813

Unknown artist

WoodLacquer

176 ⨯ 101 ⨯ 48 cm

Price on request

Zebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

- About the artworkThe Stamford Raffles Secretaires.

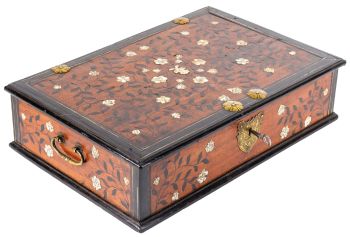

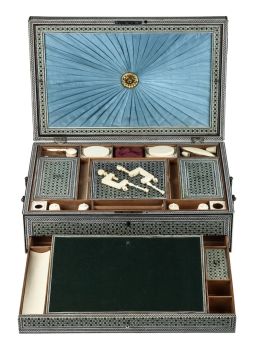

A pair of Japanese Kyoto-Nagasaki style export lacquer secretaires by ‘Lakwerker Sasaya’ each with the name ‘Olivia’

Kyoto, Edo period, circa 1800-1813

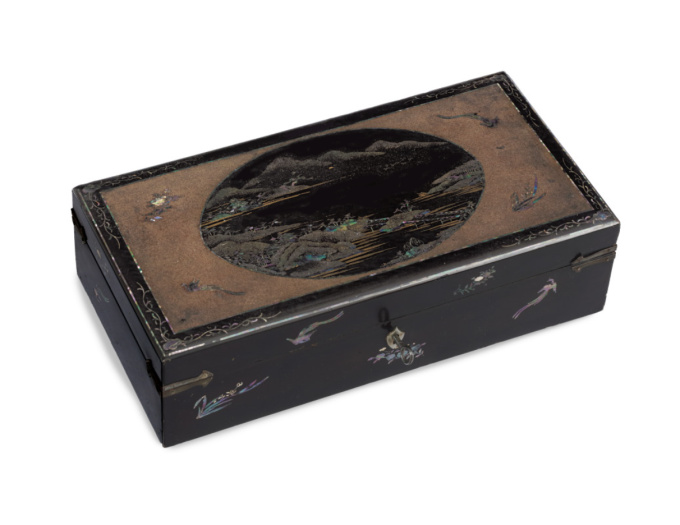

Both secretaires are made according to the French taste of the late 18th/early 19th century. However, they are fully executed in black lacquer over sugi wood (cedar, Cryptomeria japonica), decorated with gold powder, silver powder, mother-of-pearl and gilt metal mounts. They are a superb example of the Kyoto- Nagasaki style of export lacquer, featuring Chinese- inspired landscapes based upon model drawings from the Sasaya Workshop. These drawings can currently be found in the collection of the Rijksmuseum (inv. no. AK-MAK-1734-4).

The upper section of each secretaire has two doors flanked by twisted maki-e decorated columns with gilt metal bases and capitals. The capitals are perfect miniature copies after lifelike examples of the To-Kyou, the upper bracket complex, of columns in traditional earthquake-resistant temple-building, with each tiny element separately stacked. The finely drawn columns are from the early Edo period and have been reused for their fineness. Underneath a retractable board, possibly for candles, a large fall-front writing slope reveals several partitions and drawers decorated with scattered flower sprays. The inside of each fall front boldly displays the signature ‘LAKWERKER SASAYA’, written in gold within an oval border. The lower sections have two large drawers decorated with Chinese-style landscapes within an oval cartouche.

H. 176.5 x W. 101,5 x D. 48 cm (each)

Provenance:

- Probably Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles the founder of Singapore, and Lady Olivia Marianme Stamford Raffles (née Devenish); thence by descent

- Probably Olivia Stamford Raffles Villeneuve, thence by descent to the Hinson Beaver Van der Haas family

Hauteville Antiquaires, Brussels

Private collection, Paris (purchased in the 1980s/early 1990s)

Thence by descent in 2019 and sold at auction in Paris right after

Remarkably, both secretaires bear the name ‘Olivia’, written in elegant hira-maki-e penmanship on the outside, just above the fall front.1 There can’t be any doubt that the present pair of secretaires were presented to Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, as a gift for his wife Lady Olivia Mariamna Stamford Raffles née Devenish (1771-1814). However, some other options must first be explored to come to a solid provenance. To start, Olivia was a completely unknown name in the Netherlands or the former Dutch East Indies. The first Olivia, or at least the only Olivia from 1750 till 1850, registered in the Dutch East Indies, was the wife of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, who was Lieutenant-Governor of Java from 1811 to 1816.

Olivia, Olivia, and... Olivia.

There may be two alternative possible explanations for the name on the two secretaires. Thanks to Lady Raffles, the name Olivia did become popular among the anglophile Dutch in Batavia. For instance, Piet Couperus, from one of the most eminent Dutch families in Batavia (Jakarta), christened his son Willem Jacob Thomas Raffles Couperus.(2) Piet’s brother-in-law, Jan Samuel Timmerman Thyssen (1782-1823), in 1809 married Gesina Couperus and named a daughter born in 1813, Olivia Ambrosina Gesina Hendrina Timmerman Thyssen (1813 -1878) and another sister of Couperus called her son Stamford William Raffles Timmerman Thyssen. Olivia and Raffles were godparents to all three ‘Raffles’ babies of the Couperus family. Outdoing them all in Anglophiliac seal was Louis François Joseph Villeneuve, vice-president of the catholic church council in Semarang and aides-de-camp to Field Marshal and later Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels (Raffles’ predecessor). He and his wife, Jeanne Emilie Gerische, baptised their Catholic daughter on the 10th of May 1812, naming her: Olivia Mariamne Stamford Raffles Villeneuve.(3)

Soon after, Olivia Villeneuve’s father’s mission was accomplished, for he became Raffles’ comptroller. Her parents were such anglophiles (and focused on getting up higher in society) that they did their very best to find her a British husband. On 18 October 1824, Olivia Mariamne Stamford Raffles Villeneuve (at twelve years of age!) married the Englishman William Hinson Beaver in Semarang, and in 1826 their child Henriëtte Louise Beaver was born in Tegal.

Concluding, there were several Olivias in the former Dutch Indies at the time, but who would give one of these one- or-two-year-old Olivias two large secretaires as a gift? One would have to wait many years before they would be of age. This would, firstly, only be possible if the secretaires arrived in Batavia later or were stored for years. Secondly, it would only be possible if the name Olivia was lacquered in Batavia. However, the name Olivia was certainly written in hira-maki-e gold in Japan. Therefore, the secretaires were already intended for an ‘Olivia’ in Japan, but, surely not for one of the babies Olivias.

Then, the question arises whether the secretaires were ordered for one of the Olivias when they were older, even after the British occupation of Java, which can be easily answered. This type of furniture was quickly out of fashion in Europe after the downfall of Napoleon in 1815, and fashion reached the colonies much sooner than earlier thought.(4) By the time the other Olivias were not small children anymore, secretaires like the ones present were out of fashion and no longer ordered to be made. Besides, it is certain that Jan Cock Blomhoff (1779-1853) ordered the secretaires in Deshima just before Raffles became Lieutenant-Governor of Java.(5)

French in Holland, English in Indonesia, Dutch on Deshima

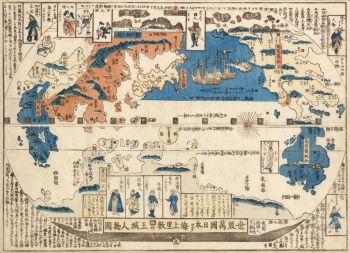

In 1792, revolutionary France attacked the Republic of the Netherlands, which capitulated in 1795.5 The Stadholder Prince William V of Orange fled to England, and the Netherlands was officially proclaimed a client state of France in 1806, becoming part of the French Empire. One of the first acts of the exiled William V, who resided in Kew Palace in London, was to write his ‘Kew letters’, instructing all Dutch colonial governors to hand over the colonies

to the British. As long as the motherland was occupied by France, Holland had to prevent France from taking possession of their colonies and trade posts. Malacca, Ambon, Sumatra, Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Guyana, and the Cape were quickly ‘occupied’ by the British without much opposition. In November 1795, an American ship brought the news of the exile of the Stadholder and his ‘Kew letters’ to Batavia. For the time being, the Indonesian city remained Dutch. Starting in 1806, the British Royal Navy maintained a blockade of Javanese ports, paralysing Dutch shipping and trade in Asia.(6)

In 1808, Napoleon appointed Daendels, a Dutch francophile republican general, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies in Batavia. with the task, among other things, to improve the defence of Java against a likely British occupation. The (again, relatively autonomous) Dutch on Java knew perfectly well that the British would try to conquer Java and that Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (based in former Dutch Malacca) strongly propagated occupying Java as a crucial step towards furthering Britain’s maritime supremacy in the Archipelago. Furthermore, it wasn’t a secret that Raffles was likely to become the British Lieutenant-Governor in Batavia and of the future ‘British East Indies’.(7)

It was only after 1817 that the first Dutch ships from Holland arrived in Batavia again under normal circumstances. Between 1799 and 1817, Holland was a vassal state later occupied by France and Dutch shipping between Holland, Batavia and Japan was almost non- existent.(8) Mainly American or Danish ships, neutral countries in the Napoleonic wars between England and France, were chartered by the autonomous Dutch authorities in Batavia to sail to Japan. The last Dutch ship, De Goede Trouw, sent by Governor-General Daendels arrived in 1809 in Japan with Jan Cock Blomhoff (1779- 1853) on board.

Jan Cock Blomhoff and Hendrik Doeff, men on a mission

In 1805, as a soldier, Jan Cock Blomhoff arrived for the first time in Batavia. Before, he had served in the Dutch military as a royalist or Orangist, supporting Stadtholder William V of Orange, fighting the French (and the francophile republican Dutch) in the Netherlands and Germany. In Indonesia, Blomhoff served in the military under Governor- General Daendels.10 On paper recognising his skills, Daendels in 1809, decided to send Blomhoff to Deshima as pakhuismeester (warehouse master) and second in rank after Opperhoofd Hendrick Doeff. One can assume that the real reason was that the Patriotic francophile Daendels probably saw the Orangist Blomhoff as a problem which needed a solution.

Blomhoff arrived with the last Dutch ship that would go to Deshima, where he met Hendrik Doeff. Doeff had arrived in Batavia in 1796 and was sent to Nagasaki as dispenser and scriba (secretary) in 1799, to become pakhuismeester and secunde11 in 1801, and finally Opperhoofd in 1803. Doeff certainly was informed by the American or Danish captains of the situation in Europe, of the ‘Kew letters’ and the likelihood of Java being occupied by the British.

Eyes on the prize: Raffles in Japan

Now that the Netherlands was occupied by France, and therefore officially French, it was thus at war with the British. The latter intercepted, wherever they could, all Dutch shipping and trade in Asia, so Blomhoff and Doeff started to get nervous on Deshima as their resources were limited. In 1811, the English occupied Java, and Thomas Stamford Raffles was appointed Lieutenant-Governor in Batavia.

Ships arrived in Japan only two times during the English period on Java, both times sent by Raffles. First, the Charlotte and the Mary in 1813 and in 1814, the Charlotte again. Dr. Donald Ainslie was sent with two ships, forcing their way into Nagasaki Bay by flying the Dutch flag and using secret signals provided by Willem Wardenaar, a former Opperhoofd who was on board together with Anthony Abraham Cassa, the intended successor of Opperhoofd Doeff. They had the order from Raffles “to take possession of the Dutch factory.”

The Dutch, as well as the Japanese, were deceived into thinking they were Dutch ships. In Deshima, although isolated from the outside world, it was nevertheless probably known that Java was occupied by the British. In his official letters, Doeff writes he was surprised, but he hardly could have been. However, one would not write such things down in official letters when the motherland is invaded by France and your Asian headquarters by the British.(10)

Raffles had furnished Ainslie with numerous presents for the “Emperor of Japan” (the Shogun), including sheep, birds, wine decanters, a clock, an Egyptian mummy, and a five-year-old elephant from Sri Lanka. The Shogun gladly accepted the gifts presented to him by Opperhoofd Doeff as if they were Dutch gift except for the clock, which was engraved with ‘barbaric’ symbols, and the elephant, which could not be lowered onto a boat and would have sunk it anyway. The Japanese came out to stare at and draw her, but she never disembarked.

Ainslie handed a letter by Raffles over to Opperhoofd Doeff demanding to hand over the factory. Doeff flatly refused, but since the factory hadn’t been visited by any ship since 1809, he owed at least 112,000 taels11 to the Nagasaki Money Chamber for merchandise he had bought, and he was more than willing to make some kind of trade settlement with the English. The English ships returned to Batavia carrying mainly copper, camphor, and, most importantly, some lacquerware.(12)

Jan Cock Blomhoff boarded the ships as well and was sent by Doeff to ask Raffles to recognise the Dutch factory and to continue the trade with Deshima under the Dutch flag. However, Raffles exploded, “how did a small servant of a state that no longer existed dare to uphold its flag and to send all the presents of the mighty Albion to the Shogun as if it were gifts from an imaginary Dutch king! What an impudence!”(13)

Doeff really couldn’t have done something else. The Japanese had allowed only the Dutch to trade with Japan, so Doeff had to pretend that the ships Raffles had sent were commissioned by the Dutch. The Japanese probably knew better - especially the local Daimyo of Nagasaki, who would rather keep up appearances than lose his life because of letting the British set foot on the Shogun’s land. Raffles, however, took revenge by confiscating the ships’ loads without sending the promised payment to Doeff and arrested Blomhoff. The British ships’ loads did include lacquerware, but there was no specific mention of secretaires. Besides, because they were British ships, no Dutch loading lists are available.(14)

It is, however, rather unique that lacquerware was mentioned, which could point towards an official order of lacquerware.(15) In the Java Government Gazette of 9th of June 1814, there was an advertisement stating that “anybody who owed or owed something to J. Cock Blomhoff from Japan should address himself immediately to J. van Reenen.” Jan van Reenen, with his own business, van Reenen & Co, in Batavia, was Blomhoff’s representative in Batavia in this case. This is a clear sign that the ships didn’t only carry copper and camphor but also held private orders of lacquerware. Either way, official order or illicit private trade, secretaires were almost certainly aboard these ships.

Four secretaires: two for the king and two for the usurper?

There is a pair of secretaires, of which one is in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (inv. NG-401) and one in the Maritime Museum in Rotterdam (M1913). They are decorated, respectively, with the depiction of the Landing of the British-Prussian troops near Petten, and with the Sea Battle of Kamperduin.(16) When Blomhoff arrived in Japan, he most likely carried the two prints after which these depictions were made. Both were published in 1800.17 This was one of the largest commissions ever made, and only a very rich or highly important person could order such exuberant pieces. Both the Sea Battle at Kamperduin and the Landing of the British-Prussian troops at Petten were victories of the Orangists, supported by the British, on the Patriot’s Batavian Republic, supported by the French. Therefore, these two secretaires, or at least two of them, may have been ordered by or for Stadholder Willem V. Doeff remained on Deshima since 1799, so it must have been Blomhoff who took the prints and ordered the secretaires.

At first glance, there are no depictions of famous Orangist victories on the Olivia secretaires. However, through close inspection by the restorers, a small section of unidentifiable maki-e that was not part of the present composition was discovered. The decision was made to take out all the panels from both secretaires and have them photographed with X-ray.(18) To great enthusiasm and surprise, the remains of an earlier decoration were revealed on each Olivia secretaire. On one, the Battle of Kamperduin can be seen, and on the other, the Landing of the troops near Petten. Now, the Olivia secretaires and the two Orangist secretaires are connected to each other, confirming the date of order, manufacture and arguably delivery.

Creating a market

It becomes clear why Doeff and Blomhoff wanted some kind of trade settlement with Raffles so badly. The Dutch owed at least 112,000 taels to the Nagasaki Money Chamber for merchandise they had bought, including four expensive secretaires. However, they would not have put all their bets on one horse. As soon as the latest news reached Deshima, whether through Chinese merchants or American or Danish ships, Blomhoff ordered the lacquer workers to redecorate the central panels of two of the four secretaires. After all, with the motherland in French hands and Indonesia in British hands, there were no future clients for the Orangist/Royalist secretaires. The battles were partially sanded down where the raden (mother-of-pearl inlay) decoration was placed, but where the background is lacquered black, the maki-e still remains behind it.

The level of craftsmanship and detail suggests that the secretaires were amongst the most precious examples of Japanese export lacquer of the era, destined for highly affluent and powerful clients. What’s intriguing, though,

is that the Olivia pair had its maki-e battle scenes erased from sight and replaced by much more politically neutral imagery of Chinese landscapes. Apparently, the original client for the two secretaires with the erased scenes disappeared from sight and had to be replaced by a new potential client. Since Deshima was completely locked off from the outside world after 1809 and badly needed money to survive and pay for the debts it was running up in Japan, Blomhoff and Doeff may have been hoping for the return of US ships like the Franklin and the Margareth who’s captains Devereux and Samuel Derby had bought many lacquered pieces of furniture in 1799 and 1801 for the American market. However, no more US ships turned up in Deshima after 1809, and all four costly secretaires remained in Deshima, unpaid for.

The redecorating of only two secretaires is an argument for the royal destination of the other pair. Often, an official order of custom-made lacquer was accompanied by an additional order of the same type or object by the official placing it. For instance, together with the pair of Deshima cabinets for Amalia van Solms in the 17th century, another single cabinet and a smaller cabinet were ordered. Presumably the first for the personal collection of the VOC official placing the order of the gifts to Amalia, and the smaller for the King of Siam, as a diplomatic gift.(19)

This is further confirmed by the provenance of the two Orangist secretaires. They both turned up in England, where

they were probably sent as presents to the Stadholder. In 1968, the Stichting Frans Wortelman bought the secretaire with the Sea Battle at Kamperduin at the Delft Antiques Fair from antiques dealer Beeling & Son, who had obtained it the previous year from the London Antiques dealers Philips Son & Neale. The secretaire with the Landing of the British- Prussian forces, according to the Rijksmuseum, was bought in the Dutch antique trade in 1958, but also came from England.

How could Sir Stamford Raffles be pleased, when he would get a ‘no’ upon his request to hand over Deshima? Perhaps by gifting (or selling, knowing the Dutch) him a pair of grande secretaires with depictions of British victories, and his wife Olivia Stamford Raffles with a pair of secretaires decorated with spectacular antique Edo-period columns and her name ‘Olivia’ finally lacquered on each of them? Research by the restorers indicates that the text ‘Olivia’

was done in Japan, but not when the secretaires were manufactured or redecorated. The only option left is that the additional writing was done in Nagasaki, by a lacquer worker connected to Sasaya.

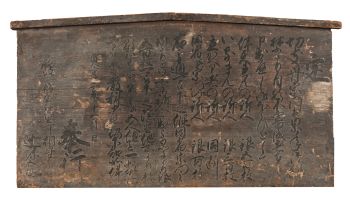

Lakwerker Sasaya

The restorers also revealed Japanese characters on the inside of the top sections, which mention a certain “Hashi Lacquer Coating Studio”, accompanied by an address in Kyoto’s Nishi-Rokujo (西六条) area. The text is particularly meaningful for export lacquer research, as it seems to confirm the long-held suspicion that Lakwerker Sasaya was not a lacquer artisan and should instead be perceived as a businessman or producer. He probably only commissioned joinery, coating, sprinkling, and pearl inlay work from various craftsmen in Kyoto before eventually moving his business to Nagasaki.

Arguably the only business doing so, he took specific orders from the Dutch based on prints they brought (possibly illegally). Based (partially) in Nagasaki, Sasaya was close to the Japanese interpreters, who were powerful within the trade but could also aid in writing Latin script on objects. Who else would be able to write ‘Olivia’ when there is no example in print? Furthermore, the lack of traces of the describing text (like on the Organist pair) on the upper panels of the Olivia secretaires, suggests that the text was lacquered later than the decoration, albeit in Kyoto or Nagasaki.

The ‘signature’ of lacquer worker Sasaya is written on at least three other items; two lacquered copper plaques,one with a scene of the Sea Battle at Dogger Bank and the other with a scene of Rome, on both is written in Dutch in gold: “verlakt bij Sasaya in Japan Ao 1792.” In the same script as on the four secretaires, “LAKWERKER SASAYA”

is signed inside a writing box decorated on the lid with the “DE REEDE VAN BATAVIA” (the anchorage of Batavia) together with the coat-of-arms of the city of Batavia, after an engraving by Matthias de Sallieth, published in 1782.20 An early occurrence of the name Sasaya is found in the ‘Dagregisters’ of 1776, where the lacquer worker Sasaija Tjobe of Kyoto is mentioned. Again, in 1778, Sasaya is mentioned, but as a ‘booth keeper’ in Nagasaki, where illegal copper was found in his storage. Lacquer worker/ dealer Sasaya was active for the Dutch between about 1775 and 1820, probably first working for Opperhoofd Isaac Titsing between 1781 and 1785, and Johan Frederik Baron van Reede tot de Parkeler between 1786 and 1789, as well as for J.A. Stutzer, a Swedish medical doctor who served

in Deshima in 1787 and 1788. In the early 19th century, Jan Cock Blomhoff probably was the most important commissioner for lacquer work by Sasaya.

Blomhoff and Raffles

In 1813, on board the Charlotte, Blomhoff went back to Batavia to try and come to some kind of agreement with Raffles about the Dutch on Deshima. However, Raffles arrested him and sent him to England as a prisoner of war. In 1814, after Napoleon had been defeated in the battle of Leipzig and the son of the Stadholder had returned

to Holland, Blomhoff arrived in London on board an English ship from Batavia, possibly with the two Orangist secretaires for the Stadholder on board. Blomhoff was set free immediately, as the Stadholder was back in Holland. Presumably, Blomhoff sold the secretaires in London.

After all, he turned out to be a businessman with ‘an open mind’. When he returned to Japan far later, he even brought a pair of camels for the Shogun, paid for by the Dutch government. However, suspiciously they never ended up with the Shogun, but travelled Japan to make money for the upkeep of Blomhoff’s Japanese ‘wife’.21

In the meantime, however, Raffles hadn’t given up on his attempts to obtain the Dutch settlement in Deshima for the British East India Company, and therefore in August 1814 sent the Charlotte, again sailing under the Dutch flag, to take possession of Deshima, as he saw many profitable trade opportunities with Japan for England. On board

again Anthony Abraham Cassa who was to replace Doeff as Opperhoofd. However, Doeff threatened to tell the Japanese that the Charlotte wasn’t a Dutch ship but a British one.

Since the British warship Phaëton, under captain Fleetwood Pellew, in 1808, flying the Dutch flag, had entered the harbour of Nagasaki, taking hostage the Dutch who came to welcome the ship. Assuming it was a Dutch ship first, which turned out to be British threatening to bombard the Chinese and Japanese ships in the bay, the Japanese authorities became very anxious about any British ship entering their harbour. They had asked Opperhoofd Doeff how to drive off the uninvited foreigners, but while they were preparing to close off the bay and to attack the Phaëton with hundreds of small vessels with burning straw, the Phaëton lifted anchor and sailed off flying the Union Jack. The Phaëton incident did cost the Japanese governor of Nagasaki his life. He committed harakiri.

The expedition of the Charlotte was as unsuccessful as the earlier attempt to take possession of Deshima, and Doeff gave Cassa a letter for Raffles stating that if the English would try again to take over Deshima, he would disclose everything to the Japanese and wouldn’t be able to protect the English against the anger of the Japanese. The Charlotte returned to Batavia with a cargo of copper and camphor, apparently paid for, or at least paying for Doeff’s court journey to Edo in 1815.

The First Lady of Java

Blomhoff was sent to London as prisoner of war by Raffles even though he already knew that Napoleon had been defeated by the Allied forces. Since the 'Kamperduin' and 'Petten' secretaires were both later, in the early 20th century, to turn up in England, Raffles could have allowed the 'presents' to the Dutch Stadholder family to be shipped with Blomhoff to London. But did Raffles accept the secretaires with Olivia’s name as a present for his wife? At least these secretaires did not later turn up in England, so presumably were not sent to London together with the Orangist secretaires, and therefore presumably remained in Batavia for the time being.

Olivia Mariamna Raffles found herself in a peculiar world upon her arrival in Java, where the upper echelons of society spoke mostly Malay and indulged in luxuries alongside primitive customs. She was taken aback by the prominence of betel chewing among high-class ladies, a habit she promptly abolished from the Governor's palace, earning the admiration and respect of society. Despite her foreign background and strict principles, Olivia quickly became a revered figure in Batavian social circles, bringing about reform and refinement in both attire and behaviour.[22]

Her influence was notable, as she encouraged the adoption of English dress over traditional garments and was celebrated for her impeccable hosting abilities at large events. Her determination and charisma allowed her to navigate the challenges of her role, garnering the affection and respect of both the Dutch and the British. Although she struggled with Java's climate and occasionally had to retreat to Salatiga's cooler environment, being severely ill often.

One example of Olivia’s popularity is the celebration of the birthday of Queen Charlotte January 18th, 1813, to which all the principal residents of Batavia had been invited a fortnight ahead. The Lieutenant-Governor and his lady, as we read in an account of the occasion, entered the hall, followed shortly after by the Army Commandant and Lady Nightingale. "The merry dance", the account runs, "soon commenced, the Major-General leading off with the ‘lady Governess,’ who we were happy to observe appeared to enjoy the dance with her usual grace and spirit". Olivia, who with her inimitable grace had devoted herself untiringly to the dance all the evening, presided later at the sumptuous supper, where four hundred guests sat, assuming the honours with supreme tact and charm. Some conception can be formed of what was required of the hostess who presided on such an occasion when is told (for instance) that there were needed: 2000 eggs, 26 ducks, 120 chickens, 666 bottles of beer, 396 bottles of Madeira, 24 capons, 72 bottles of port wine, 400 loaves of bread, two sheep, a whole cow, and a tun of salted meat.

Did Raffles and his wife decorate their Governor’s Buitenzorg (Bogor) palace with these secretaires? One for him and one for Olivia, hence the rubbed-out name on one of the secretaires? Or did Olivia receive them both as a gift? One thing is certain; she didn't enjoy them for long because she died one and a half years after receiving the secretaires, on 26 November 1814, leaving her husband a broken man.

On 25 March 1816, Raffles left Java, arriving in England on 11 July. With him, he had his books, manuscripts, animal and plant specimens and drawings, his Javanese artefacts including 450 wayang puppets, 135 masks, twenty krises, Dutch torture implements from Malacca, his sets of gamelan instruments, bronze and wooden figures, the two great heads of Buddha and other pieces from the Borobudur, plus quantities of weapons, bowls, pots, boxes, coins, textiles, charms, paddles, hats and ornaments, in all thirty tons of weight. Practically all of his Javanese artefacts eventually would end up in the British Museum. No Japanese secretaires are known to have been part of Raffles’ shipment to England, so they presumably remained in Batavia. Raffles never returned to Batavia. On the 5th of July 1826, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles died in London.

Where did the secretaires go after Olivia’s death? An account of her close friendships in the Dutch colonial community might give an answer. “[…] The sickness took a favourable turn and before the year closed she seemed to be so far recovered as to be able to receive the visits of friends. First among these were: her sister-in-law, Mrs Loftie, a sister of Raffles', who belonged to the vice-regal household.[…] To the aristocratic Dutch families in Olivia's time belonged the Couperuses, Meyers, Bauers, Vieruses, Timmermans, Thyssens, Veldhuises, Ysseldijks, Cranssens, Van Braams and Muntinghes, who were devoted, heart and soul, to the first lady in the land, foreigner though she was. It was to the Couperus family that she was most drawn and both Petrus Theodorus and his wife Catharina Rica, daughter of Cranssen, the Councillor of State and the only Hollander (besides Muntinghe) to sit in the Council during the British interregnum, were always welcome guests at the palace. Cranssen and Couperus, father-in-law and son-in-law, were great personal friends of Raffles, besides, and no one was surprised when, upon the birth of a son, the names chosen for him were Jacob Thomas Raffles Couperus.” It could well be possible that one of the godchildren named after Olivia, Olivia Ambrosina Gesina Hendrina Timmerman Thyssen (1813 -1878) or Olivia Mariamne Stamford Raffles Villeneuve (1812-1858) inherited the secretaires.

Olivia Timmerman Thyssen married Abraham Marie Bousquet (1807-1861), moved to the Hague, and remained childless. It could be that the secretaires were sold after her death, but they would probably have been taken apart and sold separately – so she inheriting them would be very unlikely. Olivia Villeneuve married William Hinson Beaver and had a daughter, Henriette Beaver (1826-1903), who died in Kampen in the Netherlands. Henriette had four children, of whom two died in the Hague after 1920 – most probably she inherited the pair of secretaires from her godmother Lady Olivia.

What happened to Blomhoff?

In 1813, after Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Leipzig by a coalition of Prussian, Russian and Austrian forces, the old Stadholder’s son, William VI, later to become King William I returned to Holland. When Blomhoff arrived in London in 1814, the peace treaty between the Netherlands and Britain had gone into effect and Blomhoff could return to Holland, a free man.

In 1816 Blomhoff was back in Batavia with his wife and son. Presumably, all (or most) of his confiscated things were returned to him by J. van Reenen, but there is no mention of secretaires. In 1817 he was to return to Deshima, as Opperhoofd and with a mission to collect Japanese art and artifacts for the newly established Cabinet of Curiosities by King William I in The Hague. He returned with his wife, Titia, small son Johannes and the Dutch wet nurse Petronella Munts, to succeed Doeff as Opperhoofd. Since the Shogunate did not allow women to stay in Deshima, Titia, Johannes and Petronella had to leave Japan on the returning ship after just over three months. Blomhoff and his wife would never see each other again.[23]

Mainly during his two Court Journeys, in 1818 and 1822, Blomhoff build up an extensive collection of Japanese art and artefacts with the aim of introducing Japanese and Japanese art, culture and customs to the early 19th-century Dutch public. During his brief sojourn in the Netherlands, Blomhoff married Titia Bergsma (1786-1821) on April 12th, 1815, in The Hague and their son Johannes was born on March 6th, 1816. During this time Blomhoff had also met Reinier Pieter van Kasteele (1767-1845), the director of the Royal Cabinet of Curiosities, King William I had established in The Hague on July 1st, 1816. They apparently discussed making a Japan collection, in accordance with the Cabinet’s mission to be ‘a place for the safekeeping of memorabilia for learning about foreign and domestic products of industry and nature.’ In consultation with van Kasteele, Blomhoff, back in Japan, collected many Japanese objects destined for the Royal Cabinet, a very early museum to collect and display objects of art and industry from Japan specifically to inform the Dutch public about the customs and material culture – as well as the natural history and minerals – of that far away and then still isolated country. This collection is now mostly held in the Rijksmuseum of World Cultures in Leiden. No lacquered secretaires are known to have been part of the Blomhoff collection for the Cabinet of Curiosities or the National Museum of World Cultures in Leiden. In 1823 Blomhoff was back in Batavia and in 1825 he returned to the Netherlands, taking part of his large collection of Japanese art and artifacts with him. Most had already been sent with earlier shipments to the Netherlands. Again, there is no trace of any Japanese lacquer secretaire in these shipments.

The final destination

The present pair of secretaires, both with the name Olivia, was recently bought together in an auction in Paris in June 2019, consigned by the descendants of a Parisian private collector right after he passed away, who had bought them about thirty years earlier in the Brussels antique trade at the end of the 1980s or early 1990s. The two secretaires apparently have always remained together.

Only a few months after the sale of the secretaires, two small export lacquer boxes from the same period appeared at auction somewhere else in France. One of the boxes has written on the inside of the lid in the typical Sasaya- style ‘OLIVIA’ in an oval reserve. Arguably, they were put up for sale by another descendant of the same Parisian collector who possibly bought the boxes together with the secretaires. These boxes could have been an order for (or of) Sir Stamford Raffles and his Olivia in addition to the two secretaires.

Where the pair went after the tumultuous period of French occupation, the foundation of the Dutch Kingdom and British/Dutch Java remains unknown, but they clearly stayed in possession of the same family for a longer period of time after being owned by the Raffles couple. It is almost impossible for a pair of large pieces of furniture

to stay together for such a long time unless, in a royal or institutional collection, they must have changed hands by sale only once or very few times – resulting in a short period with danger of being parted.

Whether they were intended as a gift primarily for Olivia Mariamna Stamford Raffles from pakhuismeester Blomhoff and Opperhoofd Doeff to placate Raffles and his wife upon Blomhoff’s arrival - to discuss the precarious (financial) situation of the Dutch on Deshima - in 1813 or not, there is no doubt that Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant- Governor of Java and founder of Singapore, purchased, confiscated, or accepted the secretaires as a gift: there is no doubt that these secretaires truly are the Stamford Raffles Secretaires.

We are grateful to Dave van Gompel, Patrick Peeters, Mamiko Masumura, Urushi Atelier Netherlands, and Lydia Randt for their insights and knowledge that contributed to the research of these secretaires.

1 On one of the secretaires, the name was severely worn and could only be read through the remnants and the underdrawings. We chose to have it reconstructed using fully reversible materials.

2 The first set of names honouring the boy’s maternal grandfather, W.J. Cranssen.

3 Jean Gelman Taylor, The Social World of Batavia: European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1983, p. 112

4 Whose existence probably were unknown in Japan anyway. 5 Susan Legène, De bagage van Blomhoff en Van Breugel: Japan, Java, Tripoli en Suriname in de negentiende-eeuwse Nederlandse cultuur van het imperialisme, Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, Amsterdam, 1998; Lydia Randt MA, ‘Een teakhouten beeld van een Europese vrouw met kind uit achtiende-eeuws Batavia’ (working title, still to be published)

6 This period is called the Patriottentijd or the ‘Time of the Patriots’ and was a period of political instability in Holland. Its name derives from the Patriots faction who opposed the rule of the stadtholder, William V, Prince of Orange, and his supporters known as Orangists. It is further important to note that the Netherlands always has been a republic, with a prince from the House of Orange as its ‘head of state’, named the Stadtholder (Stadhouder).

7 Indonesia was so profitable to the Dutch that it was highly wanted by the British and French. However, the Dutch presence on the island was still strong due to alliances with local rulers and the bad reputation of the British. The colony should be regarded as a separate factor in the Netherlands with a high degree of self- governance. After all, a certain autonomy was needed anyway, as the colony always had a hard time governing one-on-one from the Netherlands.

8 John Sturgus Bastin, Letters and Books of Sir Stamford Raffles and Lady Raffles: The Tang Holdings Collection, Didier Millet, Singapore, 2010

9 One should remember that it is not as black and white as it seems. News surely reached Deshima through Chinese ships coming from Canton, as the Chinese were also allowed to trade with Japan.

10 Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies from 1808 till 1811. 11 Secunde means second or vice-head merchant. 12 Hendrik Doeff, Herinneringen uit Japan, Bonn, 1833 13 Tael can refer to any one of several weight measures used in East Asia and Southeast Asia. In this case the ‘currency’ used by the

Dutch to trade with Japan. 14 Oliver Impey & Christiaan Jörg, Japanese Export Lacquer, 1580-

1850, Hotei Publishing, Leiden, 2006, p. 143-157 15 Albion, a literary term for Britain or England, is often used when referring to ancient or historical times. 16 From the very start of the VOC, the Dutch administration has

been well-kept, and every ship or person travelling has been registered (excluding illicit private trade, unfortunately). These papers are being kept in the National Archive in the Hague and are a god’s gift. The British, however, unfortunately, were less punctual than the Dutch.

17 Or, because of the British occupation of Java, used as more weight for the money and resources Doeff desperately needed.

18 Respectively with text Het Landen der Engelschen Tusschen Petten en Calants Oog op den Zeven en Twintigsten Augustus Des Iaars 1799 and Zeeslag tusschen de Bataafsche en Engelsche Vlooten op de Hoogte van Egmond, den 11 October Des Iaars 1797. Staande de Bataafsche Vloot onder Bevel van den Admiraal DE WINTER en de Engelsche onder den Admiraal Duncan.

19 Custom-made orders in lacquer, especially small items like tobacco, snuff or writing boxes, oval portrait medallions and larger plaques, all with depictions after European prints, were in vogue in Europe then and fetched good money. There was a lively (illegal private) trade in these items, but they are never mentioned in the dagregisters or other administrations. (Jörg, 2005)

See collection Rijksmuseum : Landing van de Britten bij Callantsoog, 1799, Cornelis Brouwer, after Jan Anthonie Langendijk Dzn (inv. no. RP-P-OB-86.723) and Zeeslag bij Kamperduin (midden), 1797, Reinier Vinkeles (I), after Gerrit Groenewegen, 1798 (inv. no. RP-P-OB-64.553)

20 We are grateful to René Gerritsen of Art & Research Photography in Amsterdam for his assistance.

21 Sir Thomas Raffles, The History of Java: vol II, second edition, London, John Murrat, Appendix B. XXXII – XXXVI.

22 Musée des beaux-arts Dijon, “Un cabinet japonais oublié”, in: l’Oeuvre du Mois, June, 2011; Guus Röell & Dickie Zebregs, Uit Verre Streken, Zebregs&Röell, Amsterdam-Maastricht, March/Tefaf 2023, pp. 104-111, no. 59.

23 Guus Röell, Uit Verre Streken, Zebregs&Röell, Amsterdam- Maastricht, June 2011, no. 2

24 Guus Röell & Dickie Zebregs, Uit Verre Streken, Zebregs&Röell, Amsterdam-Maastricht, November 2022, no. 54 & 56

25 Davies, ‘Olivia and Sophia Raffles’, in: Malaya in History: the magazine of the Malayan Historical Society 3, 1957, no. 2, pp. 104-107

26 R.P. Bersma, Titia. The first Western Woman in Japan, Amsterdam, 2002 - About the artist

It might happen that an artist or maker is unknown.

Some works are not to be determined by whom it is made or it is made by (a group of) craftsmen. Examples are statues from the Ancient Time, furniture, mirroirs, or signatures that are not clear or readible but as well some works are not signed at all.

As well you can find the following description:

•“Attributed to ….” In their opinion probably a work by the artist, at least in part

•“Studio of ….” or “Workshop of” In their opinion a work executed in the studio or workshop of the artist, possibly under his supervision

•“Circle of ….” In their opinion a work of the period of the artist showing his influence, closely associated with the artist but not necessarily his pupil

•“Style of ….” or “Follower of ….” In their opinion a work executed in the artist’s style but not necessarily by a pupil; may be contemporary or nearly contemporary

•“Manner of ….” In their opinion a work in the style of the artist but of a later date

•“After ….” In their opinion a copy (of any date) of a work of the artist

•“Signed…”, “Dated….” or “Inscribed” In their opinion the work has been signed/dated/inscribed by the artist. The addition of a question mark indicates an element of doubt

•"With signature ….”, “With date ….”, “With inscription….” or “Bears signature/date/inscription” in their opinion the signature/ date/ inscription has been added by someone other than the artist

Are you interested in buying this artwork?

Artwork details

Related artworks

Unknown artist

N.d. Murder of Johan and Cornelis de Witt in The Hague1672

€ 2.250Jongeling Numismatics & Ancient Art

Curated by

Curated byDanny Bree

1 - 4 / 12Unknown artist

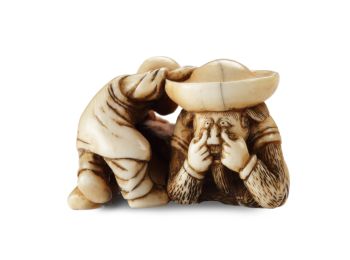

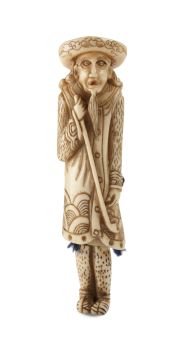

AN IVORY NETSUKE OF A DUTCHMAN FROLICKING WITH A SMALL BOY18th century

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A rare Japanese export lacquer medical instrument box1650 - 1700

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A MARINE IVORY NETSUKE OF A DUTCHMAN HOLDING A CHINESE FAN18th century

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A JAPANESE SMALL SAWASA 'PEACH-FORM' CRUCIBLE CUPearly 18th

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A IVORY NETSUKE OF A DUTCHMAN HOLDING A COCKEREL18th century

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A RARE LARGE JAPANESE LACQUERED LEATHER TELESCOPE1750 - 1800

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

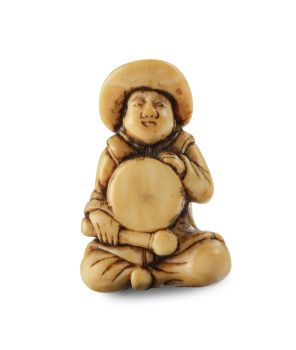

Unknown artist

A SMALL IVORY NETSUKE OF A DUTCHMAN WITH A DRUM1750 - 1800

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 21Unknown artist

AN IVORY NETSUKE OF A DUTCHMAN FROLICKING WITH A SMALL BOY18th century

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A RARE LARGE JAPANESE LACQUERED LEATHER TELESCOPE1750 - 1800

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A COLLECTION OF FOUR SRI LANKAN IVORY BIBLE BOXES18th century

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A GILT-SILVER SRI LANKAN DOCUMENT SCROLL CONTAINER 19th century

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A SMALL IVORY NETSUKE OF A DUTCHMAN WITH A DRUM1750 - 1800

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A IVORY NETSUKE OF A DUTCHMAN HOLDING A COCKEREL18th century

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A RARE COMPLETE INDIAN SADELI INLAID WORK AND WRITING BOX1800 - 1850

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 24- 1 - 4 / 24

Unknown artist

A RARE LARGE JAPANESE LACQUERED LEATHER TELESCOPE1750 - 1800

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A JAPANESE SMALL SAWASA 'PEACH-FORM' CRUCIBLE CUPearly 18th

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Theo Meier

“A Balinese woman with offerings”1936

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A COLLECTION OF FOUR SRI LANKAN IVORY BIBLE BOXES18th century

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

Unknown artist

A SMALL IVORY NETSUKE OF A DUTCHMAN WITH A DRUM1750 - 1800

Price on requestZebregs & Röell - Fine Art - Antiques

1 - 4 / 12